By Swasthika Arulingam and Lalitha Dedduwakumara

The Free Trade Zones (FTZ) were established in Sri Lanka in 1978 with the hope of bringing Foreign Direct Investments, employment to people and developing the economy under an export focused model.

The creation of FTZs saw an influx of young workers, moving from the rural villages to the FTZs with the hope of supporting their families which until then relied on farming, fishing or work at State corporations. Therefore, the flooding of workers into the FTZs was also a result of the disintegrating villages, where the rural economy, the engine of local food production was largely neglected by a State, which was now under compulsion from Free Trade Policies to import even essential foods.

The FTZs brought with it jobs, consistent wages, the formation of support services around the zone which in turn generated more employment. Therefore, in the early days despite the harsh working conditions, workers in factories were still guaranteed sustained work. The situation has changed now, with increased informalisation of work under the manpower labour system.

Despite the late 70’s Free Market State attempting to grant ‘flexible’ access to labour weakening labour laws, this did not succeed, at least on paper due to proactive Trade Union actions. The Labour Laws applicable to other workers continued to remain in force and intact for FTZ workers. Therefore on paper, the FTZ workers to date obtain a guaranteed minimum wage, compensated overtime work, mandatory holidays, protection for hazardous employment, special protection for women particularly for pregnant and feeding mothers, a ban on child labour and the right to Unionise. Despite several attempts by Employers to claim that Labour laws were ‘rigid’ and ‘outdated’ (read ‘denied the right to hire and fire at the will of the Employer’) these Labour laws have acted as a shield protecting workers from exploitation by Factories.

However, consistent public campaigns carried out by Employers to make labour laws ‘flexible’, no doubt funded by heavy advertising budgets, alongside the weakening of government agencies implementing the labour laws, have had an impact on public and Government perception on our Labour Laws.

Therefore, despite strong labour laws existing on paper, implementation of labour laws and the protection accrued to workers in practice through these laws had deteriorated over the years. The true impact of a deteriorating enforcement mechanism of labour laws became glaringly obvious to the public at large with the COVID-19 pandemic.

COVID-19 Reality for Workers

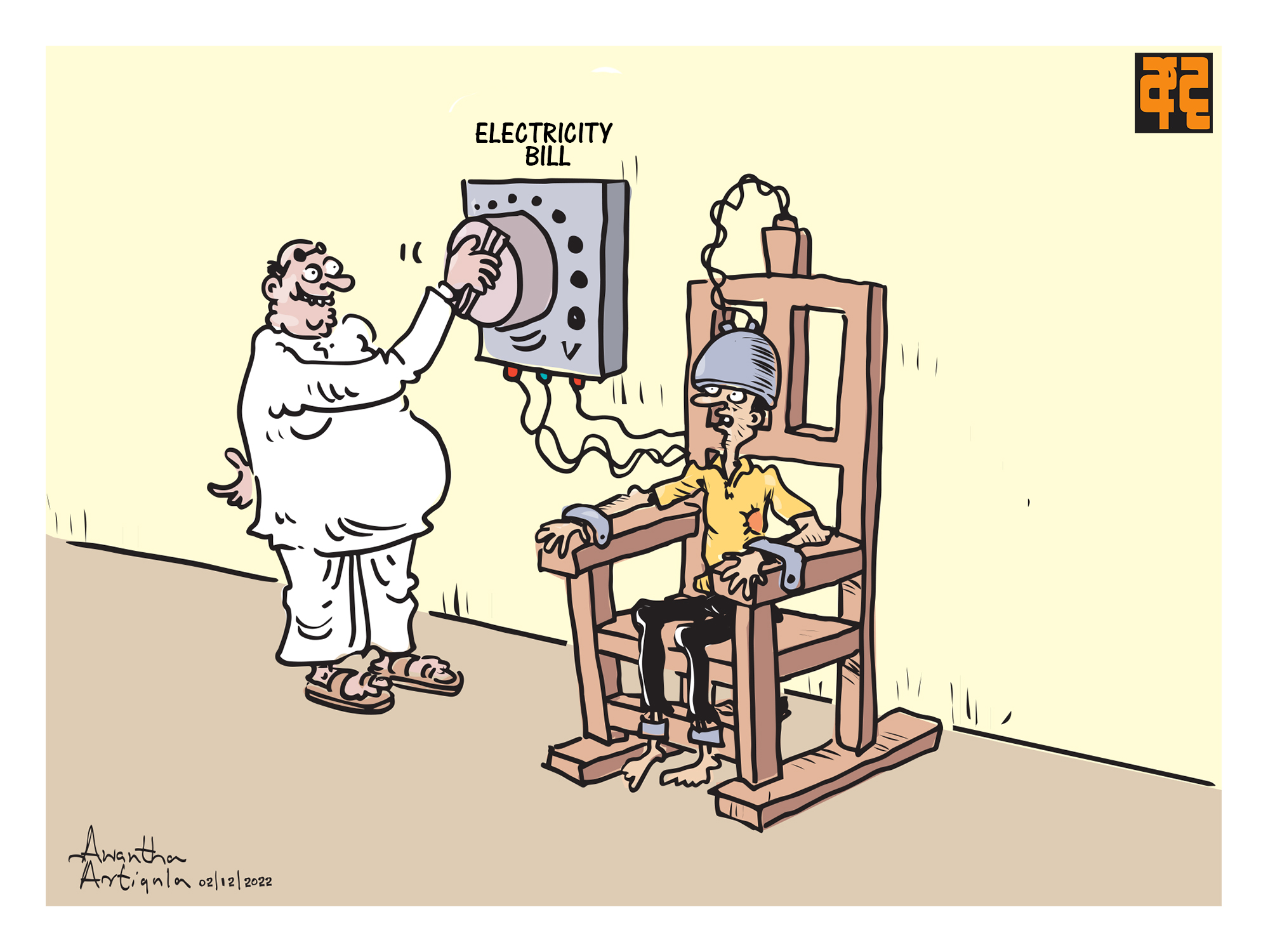

Today, loss of employment, loss of wages, health and safety issues aggravated by an unorganized and unrepresented workforce due to years of unchecked union busting activities by companies is rampant in the FTZs. Workers trapped in COVID-19 infected factories chug our failing economy whilst the rest of us stay safely inside the comforts of our homes during the pandemic.

Gampaha District in which three of the FTZs are situated report the highest number of COVID-19 cases every day. Thousands of workers including manpower workers have lost their jobs in the last two years. This is inspite of a supposedly ‘historical’ agreement between the employers, trade unions and the government to cut wages with the view of protecting jobs. In some places the job cut is as sharp as 80% which amounts to de facto retrenchment. Therefore, at the end of one and half years when the agreement was finally scrapped due to Trade Union opposition, the workers have lost wages, jobs and legally entitled compensation which could have helped them through the difficult months of pandemic.

Legally speaking this was an illegal arrangement as the only provision the law makes to cut wages is with the consent of the Employee. However this 50% wage cut arrangement which was supposed to last for two months, dragged on for almost a year despite strong opposition from the Trade Unions and the Workers. Workers struggling with medical expenses, failing health could not even afford a proper plate of food due to wage cuts. Ironically the head of the COVID-19 task force who declared a war on the COVID-19 virus had little to say to the frontline soldiers - the factory workers suffering wage cuts whilst they were placed to fight the economic crisis which came along with the pandemic.

Export sector workers, especially in the apparel sector earn a living wage only after earning production incentives, attendance incentives and overtime compensation for their basic wages. as the minimum wage of an apparel sector worker stood at only LKR 15500.00 (before the minimum wage was revised to LKR 16000 a few weeks back). Therefore with the disruption in the production process, curfews, lockdowns and isolation periods, the workers had already suffered cuts to their living wage. The cut in the basic wage, permitting the employers to cut down on wages by half was therefore a double cut to the earnings of the workers.

Compensation for Lost Wages - A Path to Economic Recovery from the Pandemic

We are no doubt in agreement that a crisis of this magnitude will result in sacrifices by the people. However, sacrifices ought to have been made depending on the ability of the person to weather the pandemic.

Garment workers in Sri Lanka protesting for full payment of wages and bonuses and respect for union rights during the #PayYourWorkers week of action, March 2021 - FTZ & GSEU

This time, however, sacrifices were made by workers alone in the form of wage cuts. They continue to make sacrifices by reporting to work at the expense of their health. While the employers pat themselves on the back for pulling out of a crisis and earning much needed foreign exchange for the economy, the sacrifices made by workers fail to garner any attention.

Although the industry as a whole faced a setback in 2020 due to disruptions caused by Covid 19, the industry is now working towards a recovery. According to the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, textile and garment exports in the first half of 2021 rose by 28% to USD 2.48 billion.

It’s time for the industries to act in the best interest of the Country and its people, return the favour to the export sector workers and start compensating for the lost wages in the form of wage increments, bonuses, COVID-19 allowance payments and the payment of full wages to those workers who are compelled to stay at home due to the pandemic.

Historically, when Countries with free market economies pull out of crises such as the COVID-19, a plan is set in motion to pull the country out of an economic slump. One consistent method in which this has been done was to increase wages. The rationale behind this economic practice is that once wages increase, consumption increases and with consumption the wheels of the market will roll. Especially in the context of Free Trade Zone and Apparel sector workers, as argued by the Indian economist Prabhat Patnaik, every cent added to their wages will be spent on accommodation, food and other locally produced goods and services. Therefore, increasing workers’ salaries not only improves the living conditions of the workers it will also generate income for local businesses and producers.

The economic thought of our companies, their factories and their think tanks, however, is still rusting in the Regan-Thatcher-neoliberal economic model, which has been long discarded even in the countries of its origin. Our factories should function to suit the demands of the 21st century and not function like archaic models of the early Industrial revolution prototype factories. Workers and Unions have long moved on assisting the economy even through a pandemic despite mounting hardship. It's high time our employers come out of the dark 80s and meet the demands of a new world.

*Swasthika Arulingam is the Deputy Secretary of the Commercial and Industrial Workers Union (CIWU). Lalitha Dedduwakumara is the Chief Organiser of Textile, Garment and Clothing Workers Union (TGCWU).