I first encountered Mr Jude Perera in late 2007 during a community discussion in Victoria. This gathering took place amidst the intense period of Sri Lanka’s prolonged civil war.

Professor Joe Camilleri of La Trobe University’s Centre for Dialogue convened the event, which marked the inception of the Sri Lanka Community Dialogue—a year-long initiative.

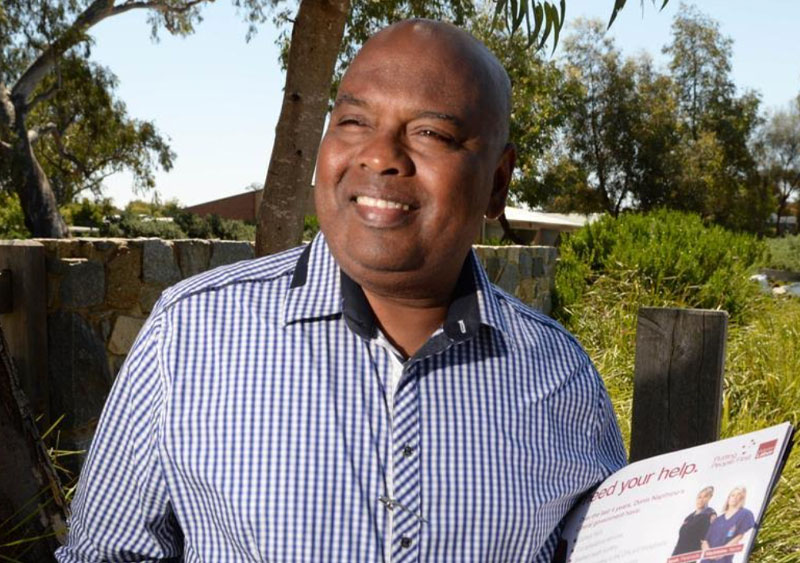

Mr Jude Perera, who recently passed away at the age of seventy-one, held a Bachelor of Science degree from the University of Jaffna. His professional journey spanned market research and information technology roles across Sri Lanka, New Zealand, and Australia. His memoir chronicled a personal and political odyssey—from Katana in Sri Lanka to Jaffna, then to Niue, New Zealand, and finally Melbourne, Australia. His travels were driven by both personal and political imperatives.

As the first Sri Lankan-born and educated migrant to serve in the Victorian State Parliament, Mr Perera achieved remarkable milestones. His unwavering advocacy for multicultural communities in Victoria led to four consecutive terms as an exemplary parliamentarian. His retirement in 2018, due to health reasons, marked the end of an era. His legacy as the first Sri Lankan-born Member of the Victorian Parliament, spanning sixteen years, remains unparalleled. While I will not delve into his political career as the MP for Cranbourne, numerous heartfelt tributes have celebrated this aspect of his life.

Our political paths diverged within Sri Lanka’s left-wing landscape. Mr Jude Perera began with the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP) before shifting allegiance to the Sri Lanka Mahajana Pakshaya (SLMP). In contrast, my journey involved the Community Party of Ceylon, followed by the Ceylon Communist Party and eventually the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) until February 1984. Our outlooks were shaped by our fathers’ political affiliations.

Central to our beliefs was a vision of a just, sustainable, and viable economy, fostering a harmonious society. Notably, Mr Perera championed worker cooperatives in his farewell address at the State Parliament. In 2015, we met to explore fairer models of production and distribution through cooperatives. While I had theoretical knowledge, Mr Jude Perera’s firsthand experiences visiting worker cooperatives in Spain, Italy, the Czech Republic, and the United Kingdom enriched our discussions. These cooperatives prioritize solidarity, democratic decision-making (one member, one vote), and holistic development—integrating management, profits, and ownership. They thrive across diverse sectors of the global economy.

Distinguishing themselves from typical cooperatives in Sri Lanka, worker cooperatives operate within a broader framework of values and principles, transcending mere profit generation. Our joint efforts, alongside Mr. Chaminda Hettiarachchi, aimed to promote worker cooperative models in Sri Lanka through the ‘New Era for Sri Lanka’ policy platform (https://www.neweraforsrilanka.org/). Regrettably, civil society in Sri Lanka did not fully embrace this transformative vision.

Worker cooperatives represent a powerful embodiment of economic democracy and social equity. However, they do not exist in isolation. Mr Jude Perera and I never advocated for businesses to operate exclusively under the worker cooperative model. Instead, we championed a diverse matrix of business models, including worker-owned and governed cooperatives, mutual aid networks, and social and solidarity economy initiatives.

Our vision centered on self-organization at the neighbourhood level, with the specific form of business design tailored to context, people, and their unique needs and goals. Jude’s unwavering focus on the future, rather than dwelling on the past, shaped his political outlook. He believed in a common political agenda that transcended personality clashes, encouraging collaboration not only with like-minded colleagues but also with those who held differing views. His succinct observation—that a political “enemy” need not be from the opposition but could sit within the same ranks—reflects his pragmatic approach.

To honour Mr Jude Perera’s legacy, we must take seriously the cooperative possibilities available to both individuals and collectives. Models rooted in the solidarity economy can generate the momentum necessary to establish and reinforce democratic practices. By doing so, we explore the potential for societies that defy major systemic inequalities and withstand periodic global crises.

Now, let us delve into the concept of the solidarity economy:

The solidarity economy aims to create and fortify economic systems that serve people’s needs while remaining ecologically sustainable, socially just, and culturally diverse. This internationalist concept emerges from the struggles of those who fight for survival and their rights within racial capitalist environments (Akuno K 2017, Build and fight: The program and the strategy of cooperation; In Akuno K., Nangwaya A. (Eds.), Jackson rising: The struggle for economic democracy and Black self-determination in Jackson, 1–20). It signifies a new relationship between society and the economy.

Key tenets of the solidarity economy include:

• Sustainable and Inclusive Development: Business models within the solidarity economy prioritize just and equitable outcomes. They place social and environmental concerns at the heart of their design. Examples include fair trade, organic trade, and circular economy initiatives. These models span a diverse network of entities, including not-for-profits, charities, cooperatives, mutuals, foundations, and social enterprises.

• Empowering the Downtrodden: Drawing inspiration from Amartya Sen’s work (Sen, A K 1999, Development as freedom. New York: Oxford University Press), the solidarity economy recognizes that marginalized individuals face limited access to opportunities. Their struggle involves challenging systems that curtail their freedoms. By deliberately coming together and engaging in collective efforts, they resist economic and political oppression.

• Global Crises and Transformation: Recent global crises have intensified interest in the solidarity economy. Questions arise about transforming existing economic models to address future challenges. In April 2023, the UN General Assembly acknowledged the critical role of the social economy in fostering inclusive and sustainable economies.

• Diverse Movements: Various movements champion the solidarity economy under different names—social economy, sharing economy, collaborative economy, steady state economy, and community economy. Their shared objective is to challenge the dominant economic system, which often relies on fossil fuels, resource extraction, and unequal wealth distribution.

In response to the shortcomings of both capitalism and state socialism, the solidarity economy emerges as a grassroots approach toward a more democratic economic system. At its core, the solidarity economy prioritizes human relationships. It rests on principles of solidarity, cooperation, mutualism, equity, participatory democracy, sustainability, and pluralism. Without embracing the ideals of a solidarity economy, genuine systemic change remains elusive. Ignoring this path risks perpetuating a reformed capitalist economy that clings to outdated neo-liberalist notions.

True political democracy cannot thrive without economic democracy. Our current democracies remain incomplete, demanding critical examination. The global economy exacerbates income disparities within and across societies. Neo-liberalism forcefully draws regions and nations into its orbit, often through economic and military coercion. This globalized neo-liberal economy teeters on the brink of catastrophe, with the spectre of a third world war and the ominous possibility of nuclear conflict threatening our planet.

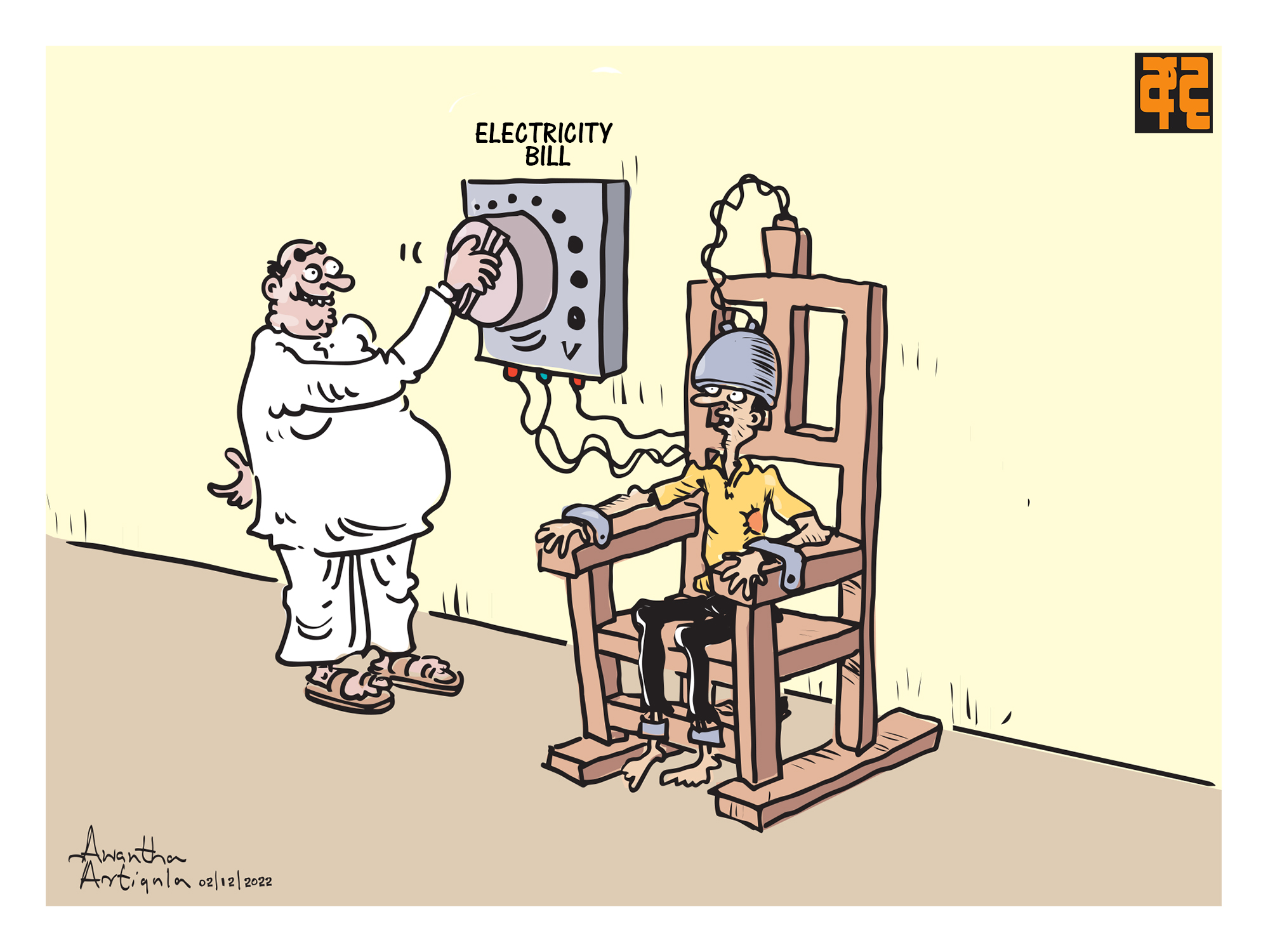

Worker cooperatives, a vital facet of the solidarity economy, offer a potent antidote to prevailing neo-liberal trends in politics and economics. Amid crises faced by many countries—including Sri Lanka—millions express dissatisfaction with their lives under neo-liberalism. Marginalised by governance systems, they grapple with social, economic, and political exclusion. Unsustainable “development” looms as a constant peril.

Worker cooperatives represent companies collectively owned and democratically managed by their workers. These cooperatives operate across diverse economic sectors worldwide. Designed to address crises and improve working conditions, they embrace less hierarchical, participatory organizational structures. In our era of interconnected economic, social, political, and environmental crises, worker cooperatives assume heightened relevance and urgency.

Fundamental to worker cooperatives are collective ownership and participatory decision-making. The world’s largest worker cooperative, Mondragon Corporation in Spain, thrived during the recent global financial crisis and beyond. Its agility and resilience contrasted starkly with conventional firms suffering due to non-democratic ownership and governance models.

Cooperative-managed institutions not only safeguard people and the planet during critical moments but also exemplify the ethical essence of economic democracy. Worker cooperatives can blaze transformative, even revolutionary, paths. Nurturing these democratic economic organisations becomes increasingly vital for humanity’s long-term survival.

Worker cooperatives wield transformative power, not only for individual workers but also for their communities. These innovative enterprises foster more equitable labour-management relationships. Workers engage in their tasks with dignity, resilience, and a sense of solidarity. What sets them apart is their multifaceted role: within a worker cooperative, individuals simultaneously function as owners, workers, patrons, and community members. This dynamic environment cultivates robust internal and external relationships.

Worker cooperatives extend beyond immediate needs, offering a blueprint for the future. They embody an inclusive, equitable, and ecologically sustainable outlook. By prioritising cooperation and solidarity, they challenge the crisis-ridden status quo. Our collective efforts must ignite grassroots movements, birthing alternative economic models capable of radically transforming the prevailing neo-liberal system. Recognizing that long-term climate resilience hinges on re-localised supply chains and community-centric economic infrastructure, we must shift away from profit-maximisation at any societal cost.

In memory of Jude Perera, let us champion “change”. Encourage, advocate, and actively transform our economic landscape. Together, we can forge a more democratic, participatory, ecologically conscious, and fair society—one that honours both humanity and the environment.

Dr. Lionel Bopage