Short-sightedness in Colombo

Expecting India to bail Sri Lanka out every time there is a crisis may work for some time, but it's a recipe for disaster.

By Harsh V Pant

During Sri Lankan Finance Minister Basil Rajapaksa’s visit to India earlier this month, the two nations have seemingly agreed to work out a cooperation package that involves broad based engagement across sectors like food, energy, investments and offer of currency swap to address the balance of payments crisis. Sri Lanka is facing an economic crisis that is increasingly becoming difficult to manage by the government.

The Covid-19 pandemic has led to a global slump with productivity dropping and supply chains getting disrupted across the world. As global food prices have risen, countries like Sri Lanka have borne the brunt given their reliance on imports to sustain themselves. Tourism sector has been hit due to the pandemic and this is a sector which generates maximum revenue for the island nation. The result has been a depreciation in Sri Lankan rupee, thereby putting more pressure on the country’s foreign exchange reserves.

Tourism sector has been hit due to the pandemic and this is a sector which generates maximum revenue for the island nation.

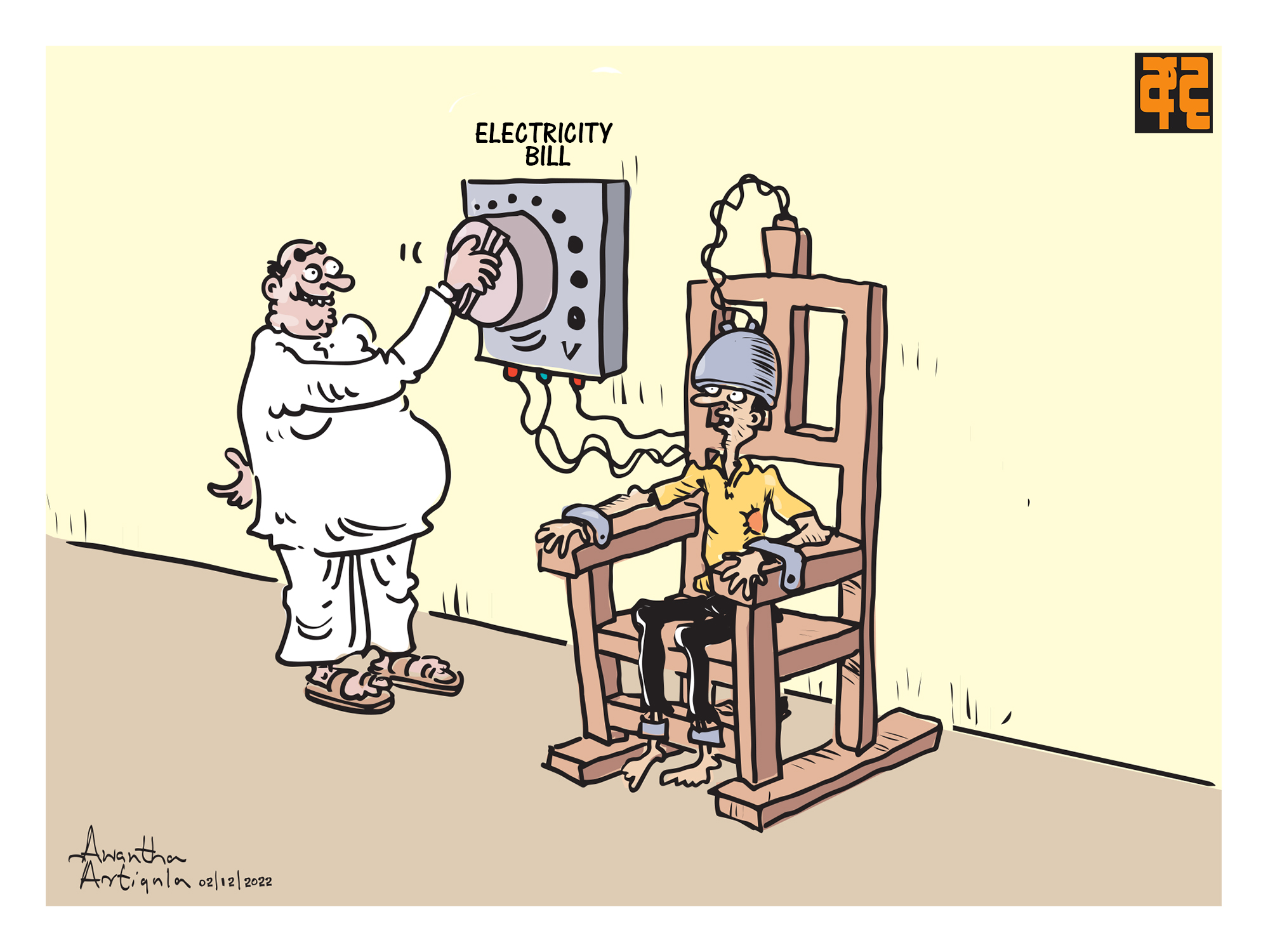

The Sri Lankan government tries to tackle this with a set of policy measures that essentially involved restricting imports and capping prices of food items that further aggravated the situation for ordinary people. Food scarcity of the kind never seen before in the country has led to widespread disaffection and questions about the ability of the government have been openly asked.

In a sign that Sri Lankan President Gotabaya Rajapaksa views this as a fundamental challenge, he admitted last month that his government was “not delivering,” suggesting that “the people may have a sense of displeasure towards me and the government for not delivering as they expected.” “I accept that,” he said in an address to the nation’s military.

But accepting the challenge and delivering the results are two different things. The Sri Lankan government has in the last few months shown a remarkable ability to repeatedly make wrong policy judgements.

Shortages of goods including kerosene oil, milk and cooking gas have led to long queues forming outside stores in Sri Lanka. AFP

There was a sudden decision earlier this year to cease imports of chemical fertilisers and pesticides to give a push to the transition to organic farming. Despite the ban having been lifted now, it has had a devastating impact on local agriculture.

Food scarcity of the kind never seen before in the country has led to widespread disaffection and questions about the ability of the government have been openly asked.

The Sri Lankan government’s mismanagement of the economy post Covid-19 is one part of the story. In some ways, most nations around the world have been impacted by the economic dislocation caused by the pandemic and have struggled to find adequate responses. That struggle continues till date with the pandemic showing few signs of abating any time soon.

The other problem for Colombo is one where China has played a big role. The attempt by the Rajapaksa government to get too close to Beijing has resulted in decisions where the only beneficiary has been China. Sri Lankan interests have been hurt and the challenge has only escalated.

It was India that had to bail out Sri Lanka with fertilisers after a Chinese company, Qingdao Seawin Biotech Co Ltd, supplied contaminated organic fertilizers, which led to the cancellation of the order. While the Chinese company rejected the allegations, Colombo argued that the samples were infected with a deadly bacteria called Erwinia which destroys crops and refused to allow a ship carrying 20,000 tonnes of organic fertilisers from China to offload the consignment. New Delhi promptly sent two IAF C-17 Globemaster aircrafts with 100,000 Kg of Nano Nitrogen to expedite the availability of fertiliser to the Sri Lankan farmers. On the other hand, a furious Beijing responded by blacklisting the People’s Bank of Sri Lanka for failing to make a payment due to a ban imposed by a local court.

Chinese investments in various infrastructure projects in Sri Lanka under the controversial Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) have been a bane for the island nation.

More broadly, Sri Lanka’s economic dependence on China has resulted in a peculiar debt-ridden relationship where mounting debt due to heavy borrowing from China has made the future of a once vibrant economy rather parlous. Most of the big projects supported by China have had a deleterious impact on Sri Lanka’s future. Chinese investments in various infrastructure projects in Sri Lanka under the controversial Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) have been a bane for the island nation. The much touted Hambantota port had to be handed over to a state-run Chinese firm in 2017 for a 99-year lease as a debt swap amounting to USD 1.2 billion.

Despite this experience, the Sri Lankan government has gone ahead and given the state-run China Harbour Engineering Company the contract to develop Colombo Port’s eastern container terminal. Not only was this done after the cancellation of the tripartite agreement with India and Japan to build this port but also suggestions in some quarters that this project under China might end up having a similar outcome like Hambantota. Too much debt for Sri Lanka and low probability of commercial success.

The challenge for Sri Lanka and India is to be realistic in their appraisal of this important bilateral partnership. Both New Delhi and Colombo are important for each other. But India will have to cease looking at every move of Sri Lanka through the China lens. For Beijing Colombo may just be a strategic outpost to outmanoeuvre India but for New Delhi this is about a long term sustainable engagement with a neighbour. For Colombo, it might be tempting to use the China card against India and get concessions. But it needs a strategic perspective in its engagement with both New Delhi. Expecting India to bail Colombo out every time there is a crisis may work for some time but it’s a recipe for disaster: both for ordinary Sri Lankans and for Delhi-Colombo ties.

*Professor Harsh V Pant is Director, Studies and Head of the Strategic Studies Programme at Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi.

This commentary originally appeared in Economic Times.