Comparing Zionism and Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism

The ubiquitous star of David across historic Palestine—on the uniforms of occupying soldiers, on checkpoints and military vehicles, on banners waved by fascist mobs chanting “death to Arabs”, on the lapel pins of politicians overseeing apartheid, on flags fluttering on West Bank settler outposts—is a reminder that non-Jewish people are at best “tolerated” by the ethno-supremacist Israeli state and at worst are to be displaced.

In 1947, Arabs held 94 percent of the land in Palestine, but with the founding of Israel the following year, 80 percent of Palestinians were turned into refugees overnight as 78 percent of the land was claimed by the new state. Today, all of historic Palestine is occupied, and Palestinians have suffered genocide comprising ethnic cleansing, pogroms, military rule, apartheid and national oppression.

For Sri Lankan Tamils, 1948 also marks the beginning of national oppression and the growth around them of an exclusionist, ethno-religious chauvinist state. Pogroms, mass displacement, inequality under the law and state violence for them are too familiar. According to Jude Lal Fernando, assistant professor in the School of Religion at Trinity College Dublin, almost 40 percent of Tamil Eelam (the Tamil homelands in the north and east of the island) is today occupied by the Sri Lankan security forces; more than three-quarters of all army divisions are located there.

In Sri Lanka, citizens live under a flag depicting a golden lion bearing a Kastane sword, a symbol of Sinhalese ethnic purity derived from the mythologies of the Mahavamsa—a sixth century chronicle of Buddhism’s history on the island. Sinhala derives from the Sanskrit Simha (“lion”). The Sinhalese, the dominant ethnic group, are lion people, sons of the soil. All others, according to the nationalist interpretation of the ancient texts, exist only by the benevolent tolerance of the majority ethno-religious group.

Like Zionism—a political movement premised on the belief that Jewish people could never live in peace unless they obtained a national state of their own—the Sinhala-Buddhist chauvinism that dominates Sri Lanka emerged as a reaction to oppression. Initially, it was a contradictory phenomenon. On one hand, the new nationalism was anti-colonial in character, motivated by a desire to reassert Sinhala language and culture and the Buddhist religion in the face of the British colonial administration of what was then called Ceylon. On the other hand, it was imbued with notions of ethnic superiority and the claim that the island was destined to be the exclusive holy land of Theravada Buddhism—an ominous prognosis for Tamil-speaking Muslims, Hindus and Christians.

From the early twentieth century, a Buddhist revival and radicalisation took shape. One of the most notable revival preachers was Dharmapala, who is reported to have gained a following among the middle classes and in rural areas. “His exhortations brought about a fanatical Sinhala-Buddhist national consciousness”, K.T. Rajasingham writes in the Asia Times. “The new wave of Buddhist awakening began to turn against non-Buddhists in general, and against non-Sinhalese in particular.” In May 1915, monks turned their attention to the country’s Muslims. The Sinhalese attacks lasted more than a week. “According to available records, losses sustained included 86 damaged mosques, more than 4,075 looted boutiques and shops, 35 Muslims killed, 198 injured and four women raped. Seventeen Christian churches were burnt down.”

The British, interpreting the pogroms as an anti-colonial rebellion, declared martial law to put down the violence and arrested scores of prominent Sinhalese leaders, among them Don Stephen Senanayake, who later became the first prime minister of independent Ceylon. “Although the burgeoning Sinhalese Buddhist nationalism and disagreements over representation had led to tensions between Sinhalese and Tamils”, notes Neil DeVotta, a professor of politics and international affairs at Wake Forest University, “their leaders maintained a united front when clamoring for independence from the British, and Sri Lanka became a free state in February 1948. None then could have anticipated the virulence and intolerance Sinhalese Buddhist nationalism would embrace”.

Almost immediately, the Sinhalese-dominated government denied citizenship to Tamils of Indian descent—more than 11 percent of the country’s population. The following year, they were stripped of the franchise. The political radicalisation of a section of the monks was only further encouraged by this. State-sponsored colonisation of Tamil lands began in earnest also. Initiating one such scheme in the North Central province, Don Stephen Senanayake is reported to have invoked “the final battle for the Sinhala people” and told the settlers that the island’s destiny was carried on their shoulders: “The country may ... forget you for a few years, but one day, very soon, they will look up to you as the last bastion of Sinhala”.

One goal was to dilute demographically the majority-Tamil areas and undermine the claims for a federal, rather than unitary, government that would have allowed political autonomy in the north and the east of the island. Many Sinhalese in the more heavily populated south were landless and endured great poverty, which made them perfect pawns in the designs of the nationalists. Malinga Gunaratne, at the time a state bureaucrat, organised one scheme into the Batticaloa district in the early 1980s. In his book For a Sovereign State, Gunaratne paints a detailed picture of how the state worked hand in glove with sections of the sangha—the Buddhist monastic orders—to motivate colonisation. Having obtained the services of a monk to lead thousands of settlers, Gunaratne describes:

“He had been chanting that most soothing melody of Seth Pirith and flying the banner of the Buddhist flag on his vehicle. He was playing on the emotions of the Sinhala people. ‘One race, one language, one religion’, seemed to be his battle cry ... he had thrown in the correct ingredients of religion, adventure and patriotism to move the settlers. They were moving to the promised land ... The warlord was not arming the people, he was doing something more effective, he was raising their spirits.”

Gunaratne favourably compares Don Stephen Senanayake and his nephew Richard Gotabhaya Senanayake (one of the country’s early trade ministers) to David Ben-Gurion and Yigal Allon, principal actors in the ethnic cleansing of Palestine and founders of the Zionist state. There are clear parallels in terms of motivation. And the schemes in many respects have had their desired effect, particularly in the Eastern province. Yet Israel was different. It was a settler-colonial state founded through the dispossession and expulsion of the Palestinians—a process that benefited the whole Jewish settler population, whose own self-determination entailed them being at once transformed into an oppressor nation. The Jewish colonists, of all classes, quite literally moved into the houses and onto the farms of the people they had expelled.

By contrast, the post-independence colonisation schemes in Sri Lanka were the fruits of an already established capitalist state. They were the logical conclusion of the radicalised politics of a section of the Sinhalese population and carried out in the name of national unity by those who had taken over the government—but they weren’t necessary for the integrity of the state or to guarantee the existence of Sinhala society in Sri Lanka. The overwhelming majority of Sinhalese, who were generally more impoverished than Sri Lankan Tamils, gained nothing from the settler schemes of the politicians and the clerics.

Sinhala-Buddhist chauvinism was in fact a distraction from the fight against their own exploitation at the hands of Sinhalese capitalists and landlords, who in part backed the schemes in order to undermine the powerful Sinhalese communist movement by expanding the base of small farmers in the country and reducing the number of landless peasants. (A failed insurrection in 1971 proved the latter to be a potent radical force that could be mobilised by the left.)

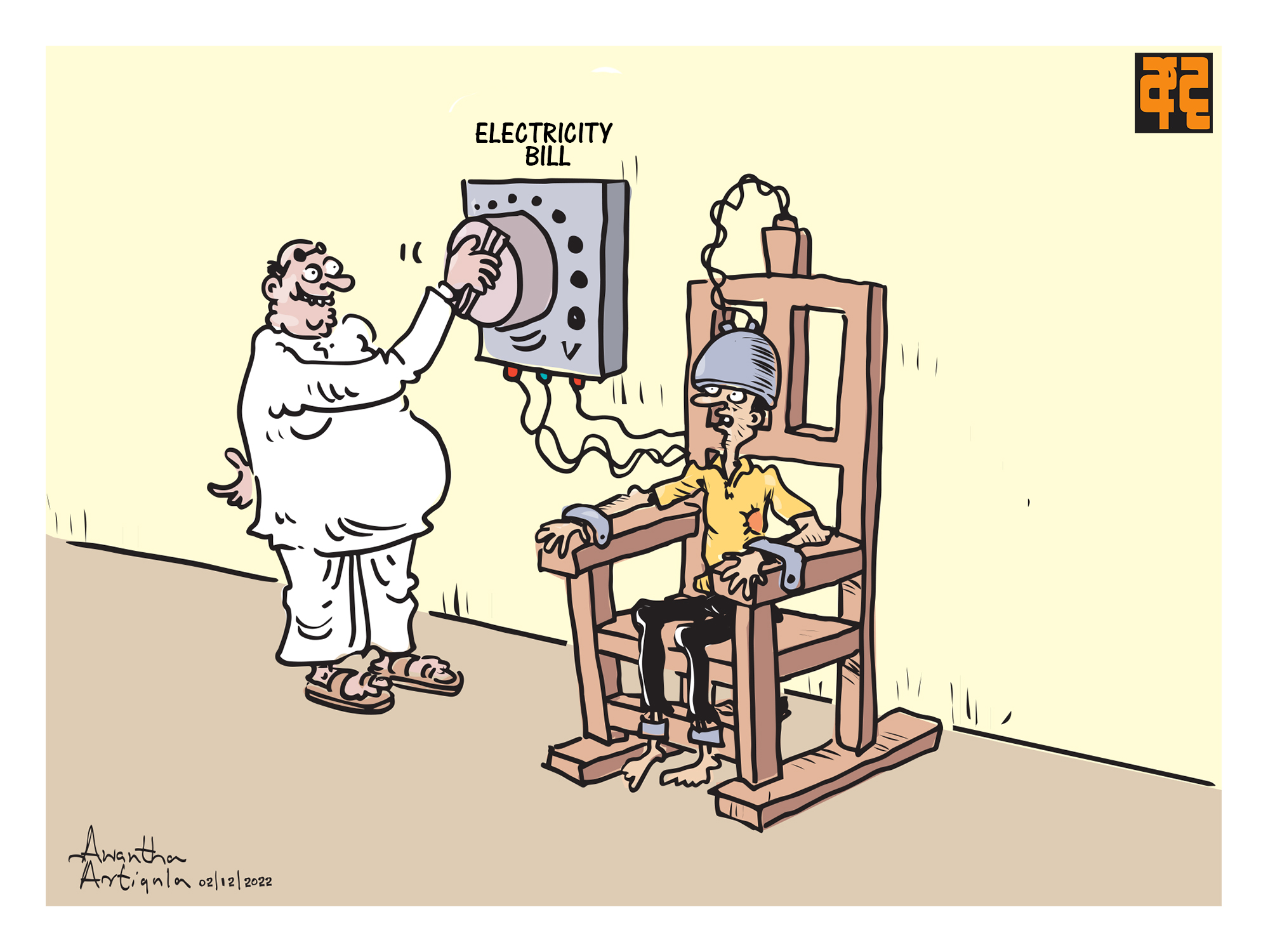

Further, the colonisation schemes were not at all the principal means of disenfranchising Tamils. The 1956 election was the turning point to that end, introducing much more effective means of oppression, when a broad coalition rallied around linguistic nationalism to make Sinhala the country’s official language. Over the next sixteen years, DeVotta notes:

“Sinhala-only was introduced to the court systems even in the predominantly Tamil north-east, and Sinhalese civil servants were stationed in Tamil areas to ensure linguistic hegemony; Tamil civil servants were forced to study Sinhala in order to be promoted; well-calibrated policies were introduced to keep the number of Tamils hired into government service extremely low; Tamils were required to score higher on exams to gain entry into the country’s universities; quota systems were introduced to increase the number of Sinhalese university students, in particular from rural areas; the government avoided allocating resources to Tamil areas and only invested in the north-east to support transplanted Sinhalese from the south who were promoting the state’s colonization designs.”

After the 1956 election, the first anti-Tamil pogrom occurred in Colombo, the capital, led by newly elected parliamentary secretary K.M.P. Rajaratne, before spreading to the Gal Oya settlement in the east. Another, more vicious, pogrom occurred two years later. The 1972 republican constitution removed the rights of national minorities and made it a requirement of the state to foster Buddhism. The lion was place on the national flag. More anti-Tamil riots were instigated in 1977 and 1981. Then came the 1983 Black July pogrom, led in many instances by monks, police and military officers. Up to 3,000 Tamils were murdered—beaten to death or burned alive—and more than 150,000 were displaced. Half a million fled the country in the aftermath, forming the backbone of the almost million-strong Tamil diaspora.

Palestinians are familiar with such developments, including discrimination against the Arabic language and within educational institutions and the state, laws making them second-class citizens, and violence at the hands of the authorities and organised right-wing zealots, led by politicians and rabbis.

Yet another similarity between Zionism and Sinhala-Buddhist chauvinism is that their proponents claim to be besieged minorities, despite Jewish and Sinhalese people making up about three-quarters of the population in their respective states, despite their governments having firmly established, officially or otherwise, relations with neighbouring countries, and despite receiving the firm backing of the large imperialist states. For the Zionists, Israel treads water in a sea of Arab hostility; Sinhala-Buddhist chauvinists similarly point to the 80 million Tamils across the Palk Strait in southern India as a looming existential threat (and the place to which Sri Lankan Tamils should “return”, which mirrors the Zionist provocation that Palestinians already have a state, namely Jordan).

There is an element of truth to the Zionist claim: mass hostility exists among Arab workers to the crimes of Israeli apartheid. More than that, the road to Palestinian liberation runs through a broader Arab uprising against the dictatorships across the region, which would allow the space to open, and material support to be forthcoming, for a Palestinian national liberation war.

By contrast, while the Tamil national liberation war (ended by the Sri Lankan military’s genocidal offensive in 2008-09) was for a time nourished, and its militants sheltered, by the Indian state of Tamil Nadu and its sympathetic inhabitants, the road to Tamil freedom does not run through Chennai, but through Colombo. Not only is the Sri Lankan capital disproportionately multi-ethnic—Sinhalese make up 37 percent of the population, Tamils 30 percent and Muslims 30 percent—but the broader region, making up one-quarter of the country’s population, is home to an impoverished and oppressed Sinhalese working class that is, unlike the Jewish population in Palestine, a natural ally of the oppressed minorities because its gains nothing from their subjugation and shares the same common enemy in the ruling Sinhalese capitalist class.

The Sinhala-Buddhist chauvinism that dominates the politics of Sri Lanka is by no means identical to the Zionist settler-colonial project in Palestine. But the similarities are many, and the results are the same: the national oppression of one group at the hands of a supremacist state run by increasingly radicalised far-right politicians who often justify their abhorrent actions in religious terms.

Ben Hillier is the author of Losing Santhia: life and loss in Tamil Eelam and The art of rebellion: dispatches from Hong Kong.