The one year remembrance of the late Mangala Samaraweera, a formidable figure in Sri Lankan politics who previously held several ministerial posts, is an apt time to reflect and learn how hard he toiled to make Sri Lanka a developed nation - both economically and socially.

This gentle humanitarian embodied a wealth of knowledge from which he emerged as the premier diplomat of the nation, trailblazing through the telecommunications and financial sectors.

Samaraweera’s first shot at politics came with the Sri Lankan Freedom Party (SLFP), where he quickly grew into a party stalwart. From the late 1980s, he campaigned for women whose sons or husbands disappeared or were killed in the Government’s crackdown against the leftist JVP that led two armed insurrections against the State.

He was a co-convener of the ‘Mothers’ Front’ movement, along with former President Mahinda Rajapaksa, raising human rights violations during Ranasinghe Premadasa’s tenure as President.

He also headed the Sudhu Nelum Movement, a peace movement under President Kumaratunga in the 1990s, where he was able to help and reconstruct the Jaffna library and hand it over to the people.

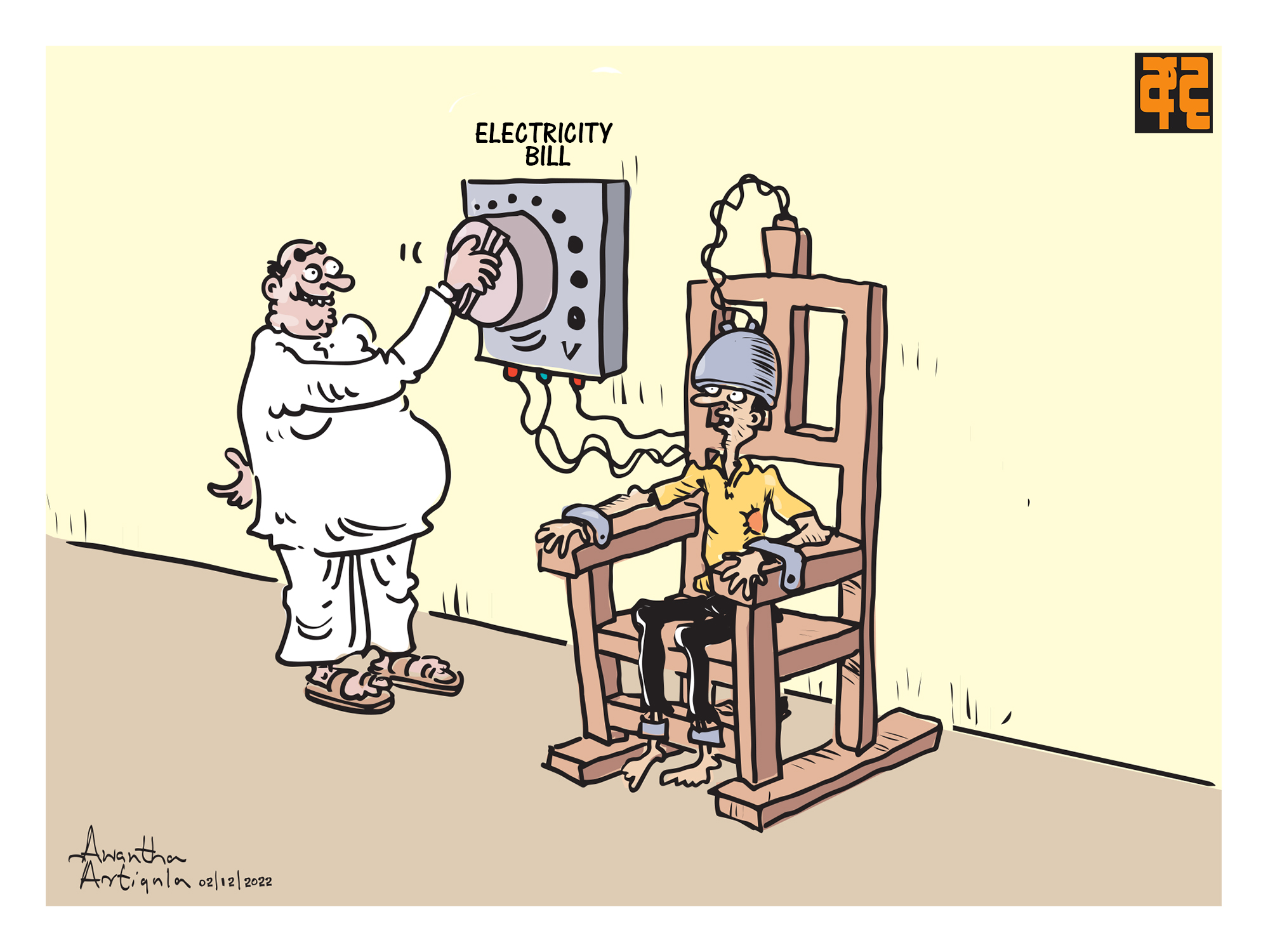

While holding the post as Minister of Post and Telecommunications Samaraweera established free market policies which are credited to have been the driving force behind achievements such as expanding telephone coverage. Before privatizing the sector, people had to queue up for 10 to 12 years to get a telephone line.

Samaraweera has showcased that he was an undoubted Sinhala nationalist on many occasions. One such instance was when he attended a 2003 demonstration against the alleged “betrayal of the Sinhala nation” by the UNP Government’s decision to sign a ceasefire with the LTTE.

Samaraweera continued to play key roles while shaping policies under former President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga. He was suppotive of the 19th Amendment and played instrumental roles in the SLFP’s seizure of power in 2003 as well as 2005.

Samaraweera played a pivotal role in calling for the ban of the LTTE abroad. Much like Lakshman Kadirgamar, Samaraweera’s management of the foreign policy establishment and deployment of its personnel needs to be commended. He had the knack to select the right people for the right tasks.

Since his links with the international community began at an early age Samaraweera was able to embrace his foreign affairs portfolio with ease during former President Mahinda Rajapaksa’s tenure.

Much like Kadirgamar, Samaraweera used his skills to drive home his message without being overbearing and by engaging his counterparts in a battle of wits, humour, goodwill and hard-core facts.

Winning back the GSP Plus trade concessions from the EU was critical to boost the economy. It was a tough task since it required tremendous work on the ground, to bring Sri Lanka’s social and human rights policies in line with UN standards, for which Sri Lanka, despite its commitments through signing on to UN treaties voluntarily in the past, had been lagging behind in implementation.

When assigned the task by the Government, to implement its human rights commitments contained in the Hundred Day Programme, Samaraweera took on the task with firm commitment. He was able to engage successfully with key concerned international interlocutors who were not ready to trust the pledges made by the Government so easily, considering Sri Lanka’s past record.

Yet, Samaraweera managed with sincerity and commitment, to engage with all sides – both local and international - and convince all of them that Sri Lanka is capable of investigating locally, all alleged rights violations, through credible, locally instituted accountability and justice mechanisms with the support of appropriate international expertise permissible under Sri Lanka’s constitutional framework.

This approach was aimed at bringing all action on alleged rights violations in Sri Lanka away and out of Geneva and New York, to be handled exclusively on Sri Lankan soil.

Samaraweera vied to create a modern Sri Lankan identity, nourished both by multi-cultural outlook of the Sri Lankan heritage and contemporary social and economic developments in the world. Unfortunately he only served two brief tenures (2005-2007 and 2015-2017) as the Foreign Minister – too brief to bring about the change he so desired.

He became an avid critic of the Rajapaksa regime after splitting up with them in 2007. His calls for democracy and the respect of human rights proved to be a window of opportunity for change.

He joined the UNP in 2010 and remained a bold voice over the last few years, critical of the Rajapaksa administration’s domestic and foreign policy.

He consistently spoke on behalf of minority rights that were under frequent attack under the Rajapaksa administration.

Another outstanding quality about this political stalwart is that he was always well read and well informed on his subject areas. Though he was an expert in many areas, Samaraweera was not someone who shunned the advice of seasoned professionals. Rather he made good use of their knowledge to uphold his own vision.

In 2020, Samaraweera resigned from Parliament politics and withdrew from contesting in the general elections under the current Opposition Leader Sajith Premadasa’s SJB party. He celebrated 30 years in Parliament on February 28, 2019.

Samaraweera was truly a man of the future and an avid humanitarian by nature and conviction. He always thought ahead of his times and committed himself to make Sri Lanka a modern, developed nation, within a short time frame.

He was widely hailed as a rare politician who stood by his principles and respected liberal values treating all equally regardless of their caste, creed, ethnicity, and religion.