COLOMBO, SRI LANKA: Sri Lankan Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapakse (R) waves to crowds 07 October 2005 in Colombo shortly after filing his nomination papers to contest the 17 November 2005 presidential elections. Thirteen candidates entered the fray, but the contest is seen largely as a battle between Rajapakse and his main challenger, opposition leader Ranil Wickremesinghe. AFP PHOTO/Lakruwan Wanniarachchi

Extensive investigations expose the mysteries and irregularities of the former defence secretary’s citizenship, visas, passports now under police probe, the Sunday Observer revealed.

Two police complaints made last week by civil society leaders about alleged irregularities in the Sri Lankan citizenship, passports and electoral registration of Gotabaya Rajapaksa have threatened to derail the presidential candidacy of the former defence secretary before it can even get off the ground.

As police investigations get underway, Sunday Observer has independently corroborated several of the concerns addressed in last week’s media reports. If criminal offences

under the Immigration Act or citizenship act are disclosed in the investigations, Sri Lanka may once again be entering ‘Helping Hambantota’ territory.

under the Immigration Act or citizenship act are disclosed in the investigations, Sri Lanka may once again be entering ‘Helping Hambantota’ territory.A few months before the 2005 presidential election, the then Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa’s presidential election campaign faced serious peril from a Criminal Investigation Department (CID) probe into the siphoning off of over Rs 60 million in tsunami aid money into a private bank account controlled by Rajapaksa’s brother’s and loyalists. That investigation was on the verge of necessitating Rajapaksa’s arrest for misappropriation of public property when Chief Justice Sarath Silva intervened, making an interim order stopping the investigation.

After Rajapaksa won the election, with the support of Silva, and the LTTE suppression of minority votes in the North and East, Deputy Solicitor General Palitha Fernando withdrew the case, telling the Supreme Court that Rajapaksa was no longer a suspect. He was later appointed Attorney-General by Mahinda Rajapaksa.

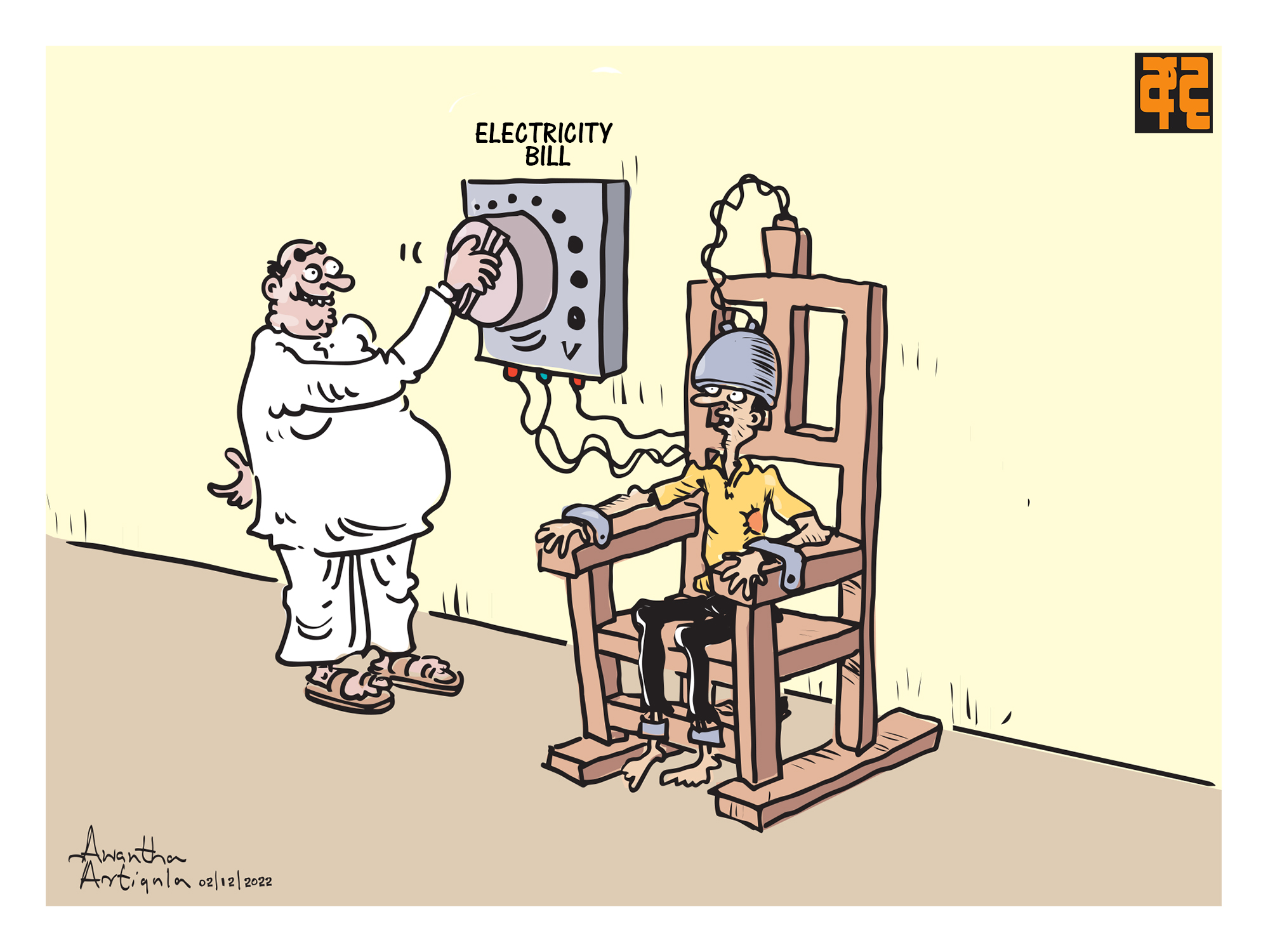

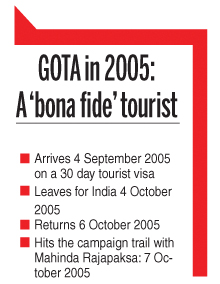

Indeed, it was while the ‘Helping Hambantota’ saga was unfolding at The Sunday Leader newspaper, the CID, and the Supreme Court, that the ‘Helping Gotabaya’ saga began. Gotabaya Rajapaksa arrived in Sri Lanka from Los Angeles on September 4, 2005. He was not a Sri Lankan citizen, having forfeit his Sri Lankan citizenship on January 31, 2003, when he became a citizen of the United States and swore allegiance to that country.

Gotabaya Rajapaksa had visited Sri Lanka several times since he became a US citizen, but did not seek to apply for dual citizenship, a status that would allow him to enjoy the rights and privileges of a Sri Lankan citizen while being an American. Instead, Rajapaksa availed himself of a perk offered by Sri Lankans to American citizens – the on-arrival holiday visa, granted to “bona fide tourists” for a period of up to 30 days.

On September 4, 2005, too, Rajapaksa entered the country on a 30-day tourist visa, purporting to be a bona fide tourist. However, in a 2015 affidavit he tendered to the Supreme Court to prevent his arrest in a glut of criminal investigations, Gotabaya Rajapaksa revealed the true purpose of his 2005 return to Sri Lanka.

“I state that, when the matters remained as such upon my brother’s bid for the presidential elections in year 2005, I returned to Sri Lanka from United States of America to assist my brother in the election campaign,” the affidavit states.

The rules of Rajapaksa’s 30-day visa were explicit. Only “bona fide tourists” could use the facility. For the avoidance of doubt, visa rules stated that “those who visit for purposes other than holiday should obtain prior visit visas” from a Sri Lankan embassy or consulate. If police investigations into recent events reveal that a person entered or remained in Sri Lanka in violation of a visa condition, such behavior would amount to an offence under Section 45 (1) (a) of the Immigrants and Emigrants Act, and carry a prison sentence of between one and five years.

“I state that, when the matters remained as such upon my brother’s bid for the presidential elections in year 2005, I returned to Sri Lanka from United States of America to assist my brother in the election campaign,” the affidavit states.

The rules of Rajapaksa’s 30-day visa were explicit. Only “bona fide tourists” could use the facility. For the avoidance of doubt, visa rules stated that “those who visit for purposes other than holiday should obtain prior visit visas” from a Sri Lankan embassy or consulate. If police investigations into recent events reveal that a person entered or remained in Sri Lanka in violation of a visa condition, such behavior would amount to an offence under Section 45 (1) (a) of the Immigrants and Emigrants Act, and carry a prison sentence of between one and five years.

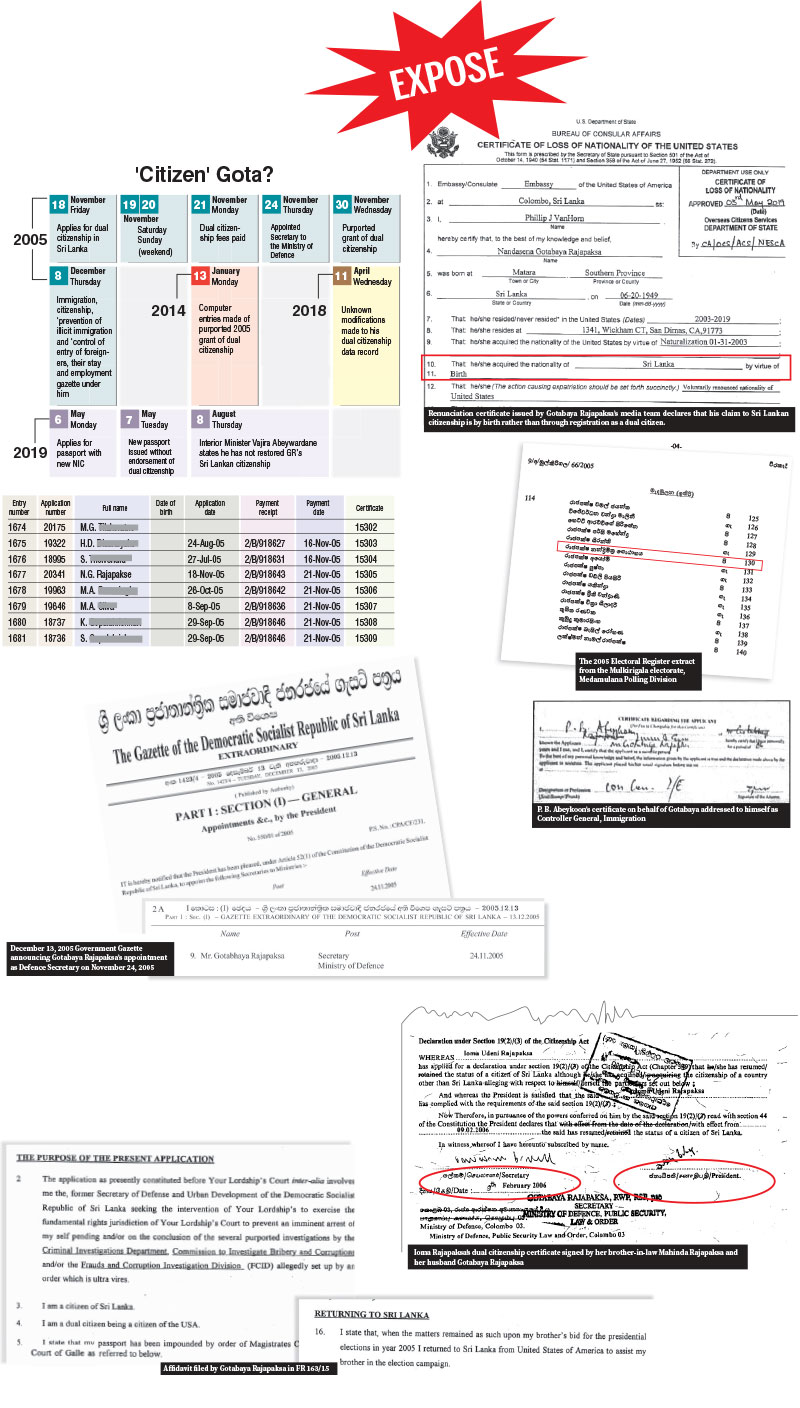

Another concern brought to the attention of the police by the complaints lodged by activists Viyangoda and Professor Thenuwara based on media reports was that Rajapaksa may have been registered to vote in the 2005 presidential electoral rolls, despite the fact that he was not a Sri Lankan citizen either when the list was compiled in 2004, or when the election was held in 2005. Sunday Observer has seen an extract of the 2005 electoral list, and confirmed that Gotabaya Rajapaksa was indeed unlawfully registered to vote from the family’s Medamulana address, despite not being a citizen of Sri Lanka. The extract has been published in these pages.

While no evidence has surfaced to indicate that he illegally voted in the election, Gotabaya Rajapaksa continued to work on his brother’s election campaign tirelessly throughout the full 30-day term of his tourist visa. As the visa was about to expire, Rajapaksa was conscious of the permitted duration of the visa, if not the permitted activities. He left Sri Lanka on day 30, October 4, 2005, to India. He was not gone for long.

After just a day in India, GotabayaRajapaksa returned on October 6. Indeed, Mahinda Rajapaksa’s nomination paper to contest the presidency was handed in shortly after his younger brother’s arrival, on October 7, 2005. He lost no time in returning to campaigning. A file photograph taken on October 7, 2005, shows the defence secretary-in-waiting at the heart of an election event with his candidate brother soon after nominations were filed.

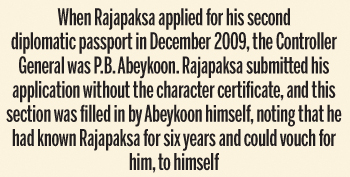

At no point in his stay did Gotabaya Rajapaksa apply for dual citizenship in Sri Lanka, until his brother, Mahinda Rajapaksa, was sworn in as president on Friday November 18, 2005. On that day, according to the “Register of Dual Citizens” book and corresponding computer database entries at the Immigration Department reviewed by Sunday Observer, Rajapaksa made an application for dual citizenship.

2005. On that day, according to the “Register of Dual Citizens” book and corresponding computer database entries at the Immigration Department reviewed by Sunday Observer, Rajapaksa made an application for dual citizenship.

In 2005, applications for dual citizenship were lodged at the Ministry office at the Immigration Department in Bambalapitiya. Applicants were required to submit a number of documents including proof of educational qualifications, birth and marriage certificates, proof of any property ownership in Sri Lanka or foreign remittance to Sri Lanka and an affidavit. These particulars were verified and security clearance was requested from the police and intelligence agencies.

2005. On that day, according to the “Register of Dual Citizens” book and corresponding computer database entries at the Immigration Department reviewed by Sunday Observer, Rajapaksa made an application for dual citizenship.

2005. On that day, according to the “Register of Dual Citizens” book and corresponding computer database entries at the Immigration Department reviewed by Sunday Observer, Rajapaksa made an application for dual citizenship.In 2005, applications for dual citizenship were lodged at the Ministry office at the Immigration Department in Bambalapitiya. Applicants were required to submit a number of documents including proof of educational qualifications, birth and marriage certificates, proof of any property ownership in Sri Lanka or foreign remittance to Sri Lanka and an affidavit. These particulars were verified and security clearance was requested from the police and intelligence agencies.

These clearance reports were then typically reviewed by Ministry officials, and after a lengthy process, a decision was made by the Ministry on whether or not to accept a dual citizenship application. Upon a decision to accept, payment of the prescribed fee, Rs. 200,000, was requested from the applicant, and a certificate was prepared to grant dual citizenship.

However, available records support the conclusion that Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s experience with seeking and purportedly obtaining dual citizenship was an entirely different one altogether. The Department of Immigration and Emigration has formally confirmed to Sunday Observer following an application under the Right to Information Act, that files pertaining to Rajapaksa’s dual citizenship are “not in the possession of this Department.”

A Department official cited a possible reason for the file’s absence being that dual citizenship matters were handled at a ministry level, however Sunday Observer has independently verified that records of most dual citizens, including the former defence secretary’s wife, Ioma Rajapaksa, are safe and sound at the Immigration Department.

In the absence of the regularly maintained files, the only records remaining to tell the story are an entry in the Register of Dual Citizens maintained by the Immigration Department, and a record in the computer database of dual citizens maintained by the Department.

According to both these sources, payment for Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s dual citizenship application was accepted in less than one working day, on Monday, November 21, 2005, indicating that his application had been accepted. The prescribed procedure, which takes several months, appears to have been circumvented in its entirety. Several applications which had been pending from as far back as June 2005 were left at the back of the queue (See Dual Citizenship Register extract)

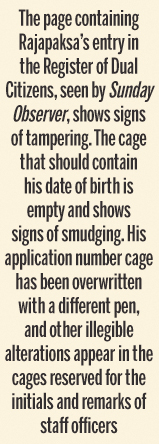

The page containing Rajapaksa’s entry in the Register of Dual Citizens, seen by Sunday Observer, shows signs of tampering. The cage that should contain his date of birth is empty and shows signs of smudging. His application number cage has been overwritten with a different pen, and other illegible alterations appear in the cages reserved for the initials and remarks of staff officers.

A Department official cited a possible reason for the file’s absence being that dual citizenship matters were handled at a ministry level, however Sunday Observer has independently verified that records of most dual citizens, including the former defence secretary’s wife, Ioma Rajapaksa, are safe and sound at the Immigration Department.

In the absence of the regularly maintained files, the only records remaining to tell the story are an entry in the Register of Dual Citizens maintained by the Immigration Department, and a record in the computer database of dual citizens maintained by the Department.

According to both these sources, payment for Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s dual citizenship application was accepted in less than one working day, on Monday, November 21, 2005, indicating that his application had been accepted. The prescribed procedure, which takes several months, appears to have been circumvented in its entirety. Several applications which had been pending from as far back as June 2005 were left at the back of the queue (See Dual Citizenship Register extract)

The page containing Rajapaksa’s entry in the Register of Dual Citizens, seen by Sunday Observer, shows signs of tampering. The cage that should contain his date of birth is empty and shows signs of smudging. His application number cage has been overwritten with a different pen, and other illegible alterations appear in the cages reserved for the initials and remarks of staff officers.

In the absence of the file containing the application for dual citizenship, supporting documents, security clearance reports, and a copy of the certificate, the only available evidence that dual citizenship was granted to Rajapaksa is the suspicious register entry and computer database records indicating that his application for dual citizenship was accepted on 30 November 2005.

However, even these entries were made, according to system audit logs, only in January 2014. It will be up to police investigators to determine what happened to the files, who made the computer system entries, and why they were made nearly a decade after Rajapaksa was purportedly granted dual citizenship.

However, even these entries were made, according to system audit logs, only in January 2014. It will be up to police investigators to determine what happened to the files, who made the computer system entries, and why they were made nearly a decade after Rajapaksa was purportedly granted dual citizenship.

Even before he was purportedly awarded dual citizenship, on November 24, 2005, Rajapaksa was made Secretary to the Ministry of Defence, Public Security, Law and Order. Gazetted under his ministry were the Department of Immigration and Emigration, and the subjects of citizenship, “control of entry of foreigners” and “controlling illegal immigration.”

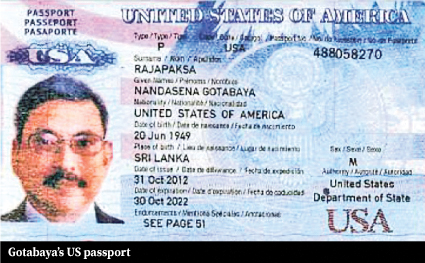

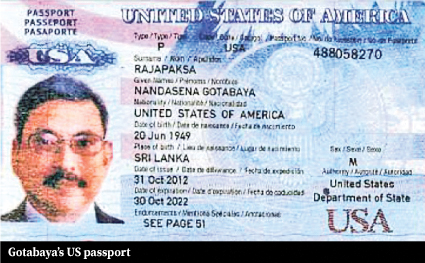

It was only six days after this American citizen was entrusted with these duties as defence secretary by his brother President Rajapaksa(See Gazette extract), that records show that his own ministry granted him the status of a dual citizen of the United States and Sri Lanka. These database and register entries appear to have sufficed to allow Rajapaksa to obtain a Sri Lankan diplomatic passport as Defence Secretary on December 20, 2005, carrying an endorsement that “Holder is a Dual Citizen”.

While passport applications by dual citizens require the applicant to furnish a copy of their dual citizenship certificate, there is no evidence on file at the Immigration Department that Gotabaya Rajapaksa ever produced a dual citizenship certificate to the department when applying for any of the five passports, three diplomatic and two regular, that he has received since he purportedly acquired dual citizenship.

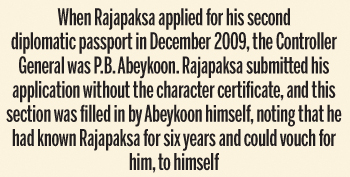

Instead, in each case, a senior immigration official has written an overriding endorsement on the application that Rajapaksa is indeed a dual citizen. His 2009 diplomatic passport application indicates the degree to which the Immigration Department saw every rule in a light favourable to Rajapaksa. At that time, passport applicants were required to obtain a character certificate from a senior public servant to present to the Immigration Controller-General, and sign the application in his presence.

While passport applications by dual citizens require the applicant to furnish a copy of their dual citizenship certificate, there is no evidence on file at the Immigration Department that Gotabaya Rajapaksa ever produced a dual citizenship certificate to the department when applying for any of the five passports, three diplomatic and two regular, that he has received since he purportedly acquired dual citizenship.

Instead, in each case, a senior immigration official has written an overriding endorsement on the application that Rajapaksa is indeed a dual citizen. His 2009 diplomatic passport application indicates the degree to which the Immigration Department saw every rule in a light favourable to Rajapaksa. At that time, passport applicants were required to obtain a character certificate from a senior public servant to present to the Immigration Controller-General, and sign the application in his presence.

When Rajapaksa applied for his second diplomatic passport in December 2009, the Controller General was P.B. Abeykoon. Rajapaksa submitted his application without the character certificate, and this section was filled in by Abeykoon himself, noting that he had known Rajapaksa for six years and could vouch for him, to himself. (See image of Abeykoon’s certificate to himself).

In this manner, his passport applications have been unique even amongst his privileged family. Even Rajapaksa’s wife, Ioma Udeni Rajapaksa, obtained dual citizenship under normal law. Records of her 2006 application and supporting documentation remain available, and a copy of her dual citizenship certificate is on file.

Ioma Rajapaksa also tendered her dual citizenship certificate (See below) on each occasion she applied for a Sri Lankan passport, as did Basil Rajapaksa, who acquired dual citizenship at a later date. Among the Rajapaksa family, it is only Gotabaya Rajapaksa whose purported dual citizenship application is shrouded in mystery.

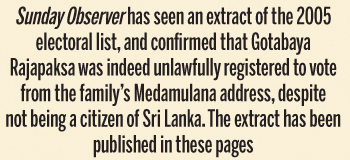

The recent events mark the first time that Rajapksa’s Sri Lankan citizenship has come under scrutiny. Attention has previously focused on his years of contradictory claims regarding his renunciation of American citizenship, a prerequisite for him to contest in the upcoming presidential elections. Beginning in 2015, Rajapaksa has made repeated contradictory claims about his renunciation of American citizenship.

However, according to California district court filings, he only submitted his application to renounce US citizenship on April 17 this year, 10 days after he was served with a lawsuit in the United States over the extrajudicial killing of Lasantha Wickrematunge.

In this manner, his passport applications have been unique even amongst his privileged family. Even Rajapaksa’s wife, Ioma Udeni Rajapaksa, obtained dual citizenship under normal law. Records of her 2006 application and supporting documentation remain available, and a copy of her dual citizenship certificate is on file.

Ioma Rajapaksa also tendered her dual citizenship certificate (See below) on each occasion she applied for a Sri Lankan passport, as did Basil Rajapaksa, who acquired dual citizenship at a later date. Among the Rajapaksa family, it is only Gotabaya Rajapaksa whose purported dual citizenship application is shrouded in mystery.

The recent events mark the first time that Rajapksa’s Sri Lankan citizenship has come under scrutiny. Attention has previously focused on his years of contradictory claims regarding his renunciation of American citizenship, a prerequisite for him to contest in the upcoming presidential elections. Beginning in 2015, Rajapaksa has made repeated contradictory claims about his renunciation of American citizenship.

However, according to California district court filings, he only submitted his application to renounce US citizenship on April 17 this year, 10 days after he was served with a lawsuit in the United States over the extrajudicial killing of Lasantha Wickrematunge.

Then, on July 30, supporters of Rajapaksa released a ‘certificate of renunciation’ on social media and on news websites, claiming that he had renounced his US citizenship at the US embassy in Colombo on July 5. The certificate was almost immediately debunked as a forgery, with Rajapaksa himself admitting the same to news outlets later the same day.

However, two days later, Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s spokesman and allied media outlets released yet another purported certificate of loss of US citizenship, which appeared more  authentic. The publication was followed by a photograph of Rajapaksa’s US passport with holes punched through it to indicate it was cancelled.

authentic. The publication was followed by a photograph of Rajapaksa’s US passport with holes punched through it to indicate it was cancelled.

Rajapaksa himself told media outlets that he had acquired a new Sri Lankan passport in May of this year that indicated that he was not a dual citizen, soon after receiving confirmation of renouncing his US citizenship. It was this revelation from him that prompted a firestorm and panicked investigations by Immigration and Internal Affairs ministry officials unaware of how he got such a passport under their noses despite being registered as a dual citizen.

According to Immigration officials, dual citizens who wish to return to becoming normal Sri Lankan citizens must make an application in that regard to the Internal Affairs Minister, who is required to consider whether granting citizenship to the applicant would be “sound public policy” after they have renounced their foreign citizenship.

But here again, Gotabaya Rajapaksa was able to find a shortcut. Had he applied for his passport in May under his existing National Identity Card (NIC) issued in 1949, the passport control computer systems would have noted that he was a dual citizen, and also that his travel documents were impounded by the Permanent High Court at Bar, where he is facing criminal charges of misappropriating over Rs 33 million in public property to build a monument and mausoleum for his parents.

Instead, Gotabaya Rajapaksa had acquired a new NIC with a new number completely detached from his previous identity card and used this number to apply for a passport. It was this passport that he used to travel to Singapore for medical treatment and miss his trial date at the Permanent High Court at Bar. The maneuver bought Gotabaya Rajapaksa time until he was able to obtain an order from the Supreme Court preventing his trial from starting until October.

Immigration investigators suspected that Gotabaya Rajapaksa obtained the irregular passport using political influence in order to sidestep the requirement of reapplying for regular Sri Lankan citizenship after forfeiting his American citizenship, because that process allows for ministerial discretion. Unlike almost any other act that permits ministerial discretion, the power of the citizenship minister to grant or revoke dual citizenship or resumed citizenship is extremely difficult to challenge in court. The citizenship act states explicitly that these powers “are final and shall not be contested in any court.”

Even the Constitution, whose fundamental rights provisions have been used to review executive decisions of other kinds, gives special exemption to the power of the minister to control the rights of foreign citizens wishing to re-pledge allegiance to Sri Lanka.

authentic. The publication was followed by a photograph of Rajapaksa’s US passport with holes punched through it to indicate it was cancelled.

authentic. The publication was followed by a photograph of Rajapaksa’s US passport with holes punched through it to indicate it was cancelled.Rajapaksa himself told media outlets that he had acquired a new Sri Lankan passport in May of this year that indicated that he was not a dual citizen, soon after receiving confirmation of renouncing his US citizenship. It was this revelation from him that prompted a firestorm and panicked investigations by Immigration and Internal Affairs ministry officials unaware of how he got such a passport under their noses despite being registered as a dual citizen.

According to Immigration officials, dual citizens who wish to return to becoming normal Sri Lankan citizens must make an application in that regard to the Internal Affairs Minister, who is required to consider whether granting citizenship to the applicant would be “sound public policy” after they have renounced their foreign citizenship.

But here again, Gotabaya Rajapaksa was able to find a shortcut. Had he applied for his passport in May under his existing National Identity Card (NIC) issued in 1949, the passport control computer systems would have noted that he was a dual citizen, and also that his travel documents were impounded by the Permanent High Court at Bar, where he is facing criminal charges of misappropriating over Rs 33 million in public property to build a monument and mausoleum for his parents.

Instead, Gotabaya Rajapaksa had acquired a new NIC with a new number completely detached from his previous identity card and used this number to apply for a passport. It was this passport that he used to travel to Singapore for medical treatment and miss his trial date at the Permanent High Court at Bar. The maneuver bought Gotabaya Rajapaksa time until he was able to obtain an order from the Supreme Court preventing his trial from starting until October.

Immigration investigators suspected that Gotabaya Rajapaksa obtained the irregular passport using political influence in order to sidestep the requirement of reapplying for regular Sri Lankan citizenship after forfeiting his American citizenship, because that process allows for ministerial discretion. Unlike almost any other act that permits ministerial discretion, the power of the citizenship minister to grant or revoke dual citizenship or resumed citizenship is extremely difficult to challenge in court. The citizenship act states explicitly that these powers “are final and shall not be contested in any court.”

Even the Constitution, whose fundamental rights provisions have been used to review executive decisions of other kinds, gives special exemption to the power of the minister to control the rights of foreign citizens wishing to re-pledge allegiance to Sri Lanka.

Article 26 (4) of the Constitution states that “no citizen shall be deprived of his status of a citizen of Sri Lanka except under and by virtue of the provisions of” the relevant sections of the Citizenship Act that provide for the loss of citizenship by persons who take on foreign citizenship, and the uncontested power of the minister to regulate the rights of such person.

Article 26 (4) of the Constitution states that “no citizen shall be deprived of his status of a citizen of Sri Lanka except under and by virtue of the provisions of” the relevant sections of the Citizenship Act that provide for the loss of citizenship by persons who take on foreign citizenship, and the uncontested power of the minister to regulate the rights of such person.Immigration investigators who conducted these initial inquiries, Sunday Observer learns, were fearful of following the prescribed procedure of reporting the irregularities to the CID for investigation. One officer said that with the former defence secretary’s presidential candidacy looming, they feared reprisals against themselves and their families were Rajapaksa to become president, especially as he seemed to enjoy allies across the political and judicial spectrum.

The official specifically recalled the Helping Hambantota scandal from the 2005 presidential election of MahindaRajapaksa, and how the Supreme Court stepped in to prevent his arrest in 2005. “This is not Mahinda. We know who this is. The Supreme Court has never allowed him to be arrested before. If they stop him again and he wins, we could be killed. We have to put our families first,” he said.

Viyangoda, who lodged the police complaint, said he believed this case was more important than Helping Hambantota allegations faced by Mahinda Rajapaksa in 2005. “In 2005 when Mahinda Rajapaksa contested for President we did not know much about crimes or corruption committed by him. Then Helping Hambantota came about and he used Sarath Nanda Silva to absolve himself,” Viyangoda told the Sunday Observer. He added that knowledge about Gotabaya’s alleged criminal activities is “100 times more” than what was known of Mahinda in 2005. “Therefore we must take greater care. We must learn a lesson from the Helping Hambantota case and ensure these charges are thoroughly investigated,” he added.

However, with the police now formally informed of the irregularities through the courageous complaints of Prof Viyangoda and Thenuwara, it will be up to sleuths to determine whether any one or more of these mysterious events surrounding Rajapaksa’s passports, citizenship or electoral status amount to criminal activity, or would affect a determination on whether indeed he is a citizen of Sri Lanka, and entitled to contest in a presidential or parliamentary election.

Viyangoda told the Sunday Observer that if Gotabaya Rajapaksa had taken dual citizenship illegally or has relinquished dual citizenship in an illegal manner or has obtained a new passport and NIC in an irregular manner, such a person could become the President of Sri Lanka. “If he acts with such impunity before gaining power, and then goes on to become President nothing will happen in a lawful manner in the country. For example there are corruption and criminal allegations against Rajapaksa. For the last several years he has used various tactics to prevent court proceedings into the corruption allegations against him. This time it is not just about corruption but it is about the future of the country. That is how I see it,” he added.

Viyangoda told the Sunday Observer that if Gotabaya Rajapaksa had taken dual citizenship illegally or has relinquished dual citizenship in an illegal manner or has obtained a new passport and NIC in an irregular manner, such a person could become the President of Sri Lanka. “If he acts with such impunity before gaining power, and then goes on to become President nothing will happen in a lawful manner in the country. For example there are corruption and criminal allegations against Rajapaksa. For the last several years he has used various tactics to prevent court proceedings into the corruption allegations against him. This time it is not just about corruption but it is about the future of the country. That is how I see it,” he added.

*The article was published on the Sunday Observer on 11 August 2019.

Related News: